MINCEMEAT

The story of one of the great Allied deception plans of World War II.

“The body was placed in the water at 0430 in a position 148° Portil Pillar 1.3 miles approximately eight cables from the beach and started to drift ashore.”

— Lieutenant Norman A. Jewell, commander, HMS Seraph

OFF THE COAST OF HUELVA, SPAIN

APRIL, 1943

On an overcast day in April 1943, twenty-three-year-old José Antonio Rey Maria rowed out from his coastal Andalusian village into the Atlantic Ocean looking for sardines. Instead, he found a body.

Shocking though it was, his discovery was far from out of the ordinary. World War II raged beyond Spain’s coastal headwaters. Out there, German U-Boat ‘Wolf Packs’ hunted Allied transport convoys with fierce regularity, hoping to sever the vital arteries of supplies, equipment, and manpower destined for campaigns around the globe. The nearest was unfolding just inside the Mediterranean—a bitter struggle to expel the Axis from North Africa. With all the air and naval traffic required to sustain such an effort, casualties were almost inevitable.

José found the uniformed, face-down body suspended on the water’s surface by a yellow life jacket. Odorous putrefaction washed over the fisherman. Holding his breath, he grabbed the saturated corpse. It bobbled and flipped, revealing a half-decomposed, half-burnt visage covered in slimy green mold.

José’s fellow fishermen wanted nothing to do with his catch. Struggling, he hauled the body halfway over the gunwale of his skiff, secured it to the stern, and rowed back to his village alone. Offloading the man on the Playa de Portil, José and another fisherman dragged him onto a sand dune, depositing him in the shade of a pine tree overlooking the ocean.

Waiting for authorities to arrive, a growing assembly of villagers speculated over the man’s origins. Who was he? At over six feet tall, the white, uniformed man wore a khaki overcoat, dark boots, and, most curiously, a black briefcase chained to his belt. Soon a group of Spanish soldiers arrived to take the body to their post in Huelva. Loading the man onto a donkey, flies hovered in the air as townspeople spoke in hushed tones.

As it turned out, the man was not a fighter, but a fiction—the brainchild of a creative batch of British Naval intelligence officers eager to preserve the secrecy of future Allied operations in the Mediterranean. With the North African campaign winding down, within two months the Allies would assault the island of Sicily. Much hinged on the invasion’s success: Harboring hopes of knocking Italy out of the war, the Sicilian landings represented the first meaningful Allied attack on Hitler’s “Fortress Europe.” Looking ahead, it offered promising avenues for continued military operations on the continent.

Preserving the Allied secret demanded desperate measures. Drawing inspiration from a 1937 mystery novel in which a bright British inspector attempts to identify a dead man porting forged papers, Rear Admiral John Godfrey, Director of Britain’s Naval Intelligence Division, and his personal assistant, Lieutenant Commander Ian Fleming wondered whether such a plan might actually deceive the Nazi’s into believing the invasion would come elsewhere—maybe the Balkans, or Greece.1

Operation Mincemeat—as their plan became known—ballooned into an elaborate ruse. 2 To lend credence to the deception, layers of misleading radio traffic and leaked rumors painted Greece as a viable Allied target; Greek linguists, maps, and currency appeared in London; a fictitious British army even surfaced within striking distance of the Peloponnese.

The keystone of the operation, however, was the planted body whose classified correspondence would confirm Axis suspicions. And to plant a body, one needed a body.

The task of acquiring one fell to thirty-eight-year-old Lt. Commander Ewen Montagu, a member of Britain’s Naval Intelligence Division, and twenty-five-year-old Charles Christopher Cholmondeley, a bespectacled RAF intelligence officer attached to MI5. Creating a convincing backstory left little margin for error. The duo needed an intact, military-age cadaver, killed recently in an innocuous, easily obscured manner, with no immediate circle of friends or family to mourn his loss—a tall task.

To their great astonishment, on January 28, 1943 an informed St. Pancras coroner alerted them to an acceptable candidate.

Thirty-four-year-old Glyndwr Michael led a hard life. Born in Wales on January 4, 1909, he spent his life in abject poverty. Moving from one dilapidated dwelling to another, he and his two siblings witnessed the grinding, traumatizing decline of their syphilatic coal-miner father, who, invariably drunk and depressed, died of influenza in 1924. Four months prior, he had attempted suicide in front of his children, burying a knife into his own neck.

Michael was sixteen at the time. While his siblings married and moved away, he lived with his mother for sixteen additional years, working as a part-time laborer and living off alms and charity donations until she, too, died—this time from a heart attack.

Alone and unstable, Michael disappeared. Eventually, he came to London. Living out of an abandoned warehouse near King’s Cross, on January 24, 1943 he ingested rat poison and died in a hospital four days later.

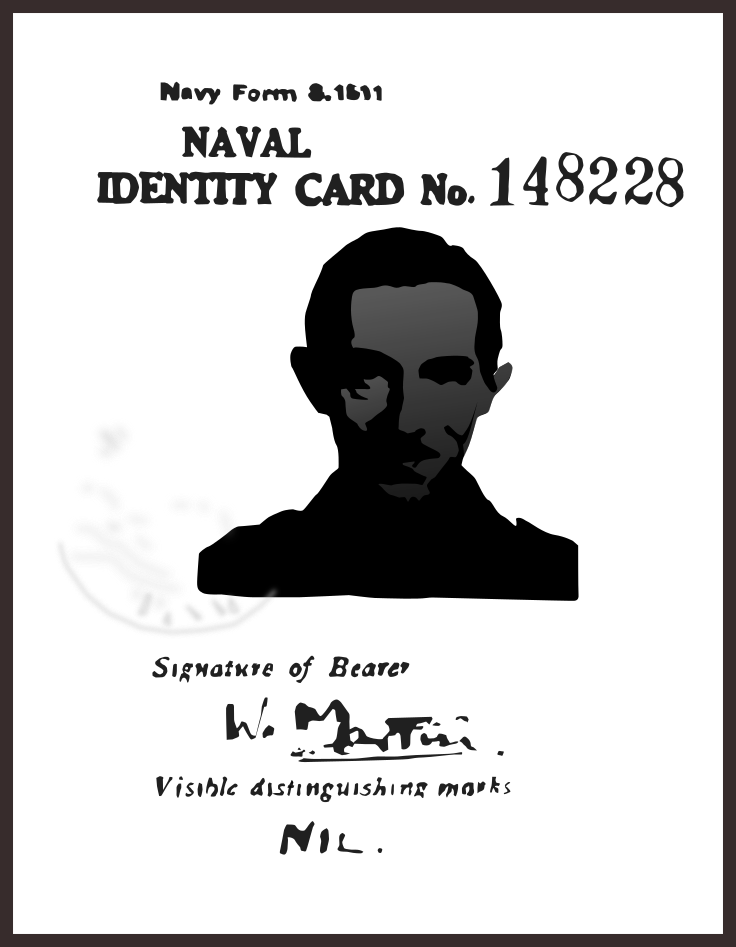

In life, Michael was forgotten; in death, he found new life. The coroner refrigerated Michael’s body for three months while Montagu and Cholmondeley fabricated a new identity for the peripatetic Welshman: Major William Martin.3

By mid-April, the duo had finalized plans for Michael’s body. They outfitted him as an upper-middle class Royal Marine courier posing as a member of Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations Headquarters. At the last minute, they found a doppelgänger to pose for an ID photograph. They filled Michael’s pockets with ticket stubs and personal letters from an imaginary fiancée, planting classified planning documents revealing Greece and the Balkans as the primary Allied target in his briefcase.

On April 18, 1943, Michael was loaded into an airtight, 400-lb dry-ice lined steel canister, driven north to Holy Loch in Greenock, Scotland, and placed aboard the HMS Seraph, a British submarine bound for Spain.

Anxiety abounded during the Seraph’s ten-day voyage. The gambit ran a high risk of failure. The submarine might encounter trouble or break down; the life vest might deflate; the body might sink. In the eventuality someone discovered Michael, there was every possibility German intelligence might easily see through his fictitious persona.

Aboard the Seraph, only its commander, twenty-nine-year-old Lieutenant Norman L.A. Jewell knew the canister’s true contents. He told his crew the mysterious case marked “Handle with Care” carried an experimental weather-reporting device they would deposit for extensive testing off the Spanish coast. Hefting the weighty, tubular canister into a forward storage chamber, six crewman “joked about ‘John Brown’s body’” and their “new shipmate, Charlie” inside what looked eerily like a metallic casket.4 If only they knew.

Shortly after 4:00 a.m. on April 30, the Seraph surfaced 1,600 yards from shore. Standing on the casing with four officers, Jewell ordered the rest of his fifty-man crew to stay below decks. Through morning mist they saw dimly silhouetted fishing boats operating in the bay. The Seraph was undetected.

It took ten minutes to open the canister. While they loosened bolts with a wrench, Jewell revealed his secret. It was a sobering announcement. Unraveling the corpse from its blankets, the officers found Michael more decomposed than expected. Some reasoned the decay lent a validity to his fictitious status as a drowning victim at sea. It would have to do.

Together, the five officers lifted Michael out of the container, inflated his life vest, double-checked his briefcase, and slid him gently into the water. Out of respect, Jewell offered a parting prayer from Psalm 39. The scripture carried as much significance for them as it did for their silent passenger: “I will keep my mouth shut as it were with a bridle: while the ungodly is in my sight. I held my tongue and spake nothing: I kept silence, yea, even from good words; but it was pain and grief to me.”

The five reentered the submarine through the conning tower. Turning the craft seaward, Jewell used the underwater current from its rotating screw to prod Michael toward his final destination. Hours later, a curious José Antonio Rey Maria, mistaking the body for a dead porpoise, hauled the Allied bait ashore.

British intelligence chose Martin’s destination with great care. Within the small city of Huelva lived an eclectic range of Axis collaborators fed regular information by groups of Allied sympathizers. With so much furor raised by Michael’s arrival, it did not take long for enemy agents to bite.

When the body arrived in Huelva, a Spanish naval officer took charge of Martin’s personal effects, sending the locked briefcase up the chain of command and the body to the local mortuary for examination. A doctor confirmed the intended cause of death: Per his report, between five and eight days prior the courier fell into the sea alive, perishing from asphyxiation while immersed in seawater.

Communicating with the British Naval Attaché in Huelva, Montagu and Cholmondeley learned that at noon on May 1, 1943, Major William Martin was given a full military funeral at Huelva’s Cemeterio de la Soledad in a ceremony attended by Spanish and British civil-military authorities.5 The attaché made no mention of the briefcase’s contents, but over the ensuing weeks a fuller picture emerged tracing their journey through neutral Spain’s military hierarchy and, amazingly, their subsequent leak to German intelligence.

When “Major Martin’s” correspondence eventually made it back to London, a battery of scientific testing confirmed they had been tampered with. In the interim, the Germans made quick use of their discovery; after photo reproductions of the classified documents made their way to the Führer’s desk, Nazi commanders diverted several divisions from Sicily, doubling their garrison at Sardinia while transferring 90,000 soldiers to Greece and the Balkans. In a telegram to the Prime Minister, Montagu pithily wrote, “Mincemeat swallowed rod, line, and sinker.”

It is impossible to know how the July 9, 1943 assault on Sicily might have fared against the combined weight of these enemy forces, just as it is impossible to know how much their redirection was directly attributable to Mincemeat. While today, historians agree that the body of Glyndwyr Michael markedly contributed to preserving the secrecy of the true Allied target—potentially even saving thousands of lives—at the time Allied leaders could do little more than hope their outlandish deception plan worked.

NOTES

Thomson’s novel was entitled The Milliner’s Hat Mystery. Fleming would later go on to author the James Bond series. ↩︎

Mincemeat inspired several future literary works, including Operation Heartbreak by Duff Cooper (London: Pan Books, 1950); Ewen Montagu’s famous inside account, The Man Who Never Was (London: Evans Brothers, 1953), and Ian Colvin’s The Unknown Courier (London: William Kimber, 1953). ↩︎

British intelligence arrived at this name using an actual roster of Royal Marine officers. Captain William Hynd Norrie Martin, promoted to major in 1941, was of sufficient rank to carry secret documents and was thus chosen. A pilot of good report, he was then serving as an instructor to American aircrews in Rhode Island and, consequently, would not know his identity had been reappropriated. Using Martin’s real-life service on an aircraft carrier sunk in 1942 as a pretext to create a vague death notice, the British hoped to convince German authorities he died by drowning. See Macintyre, Operation Mincemeat, 64–65. ↩︎

Ewen Montagu, The Man Who Never Was, 72. ↩︎

Later on, Montagu arranged for the Naval Attaché in Huelva to deposit a wreath on Martin’s marble tombstone. In homage to the unknown warrior, the tombstone read: “William Martin. Born 29th March 1907. Died 24th April 1943. Beloved son of John Glyndwyr Martin and the late Antonia Martin of Cardiff, Wales. Dulce et decorum west pro patria mori. R.I.P.” In 1998, the British Government finally amended the tombstone to reflect its occupant’s true identity: “Glyndwyr Michael; Served as Major William Martin, RM.” He rests in Huelva to this day. ↩︎

READ MORE

Ben Macintyre, Operation Mincemeat: The True Spy Story that Changed the Course of World War II (London: Bloomsbury, 2010).

Denis Smyth, Deadly Deception: The Real Story of Operation Mincemeat (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Richard Compton-Hall, Submarines at War, 1939–45 (Cornwall: Periscope Publishing, Limited, 2004).

Ewen Montagu, The Man Who Never Was (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1953).