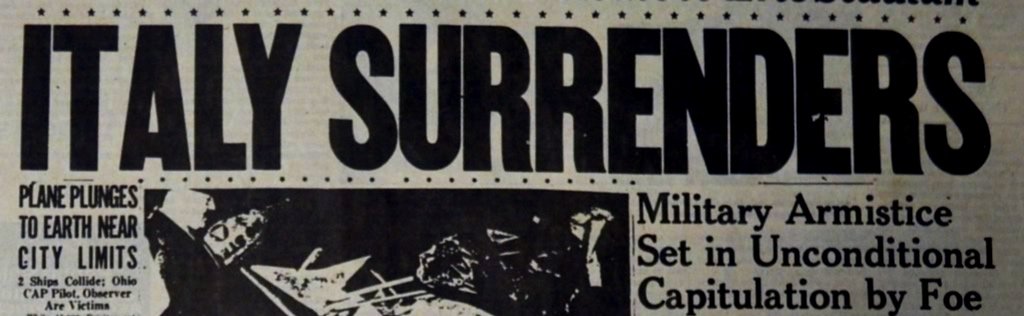

If This Folder Could Talk: The Compelling Story of Italy’s Secret Surrender during World War II

Published in the Summer 2022 issue of Marshall Magazine.

Available here.

Archival visits are a lot like treasure hunts. Filled with the prospect of documentary riches, most researchers—like treasure hunters—know there is no promise long hours of investigation will yield rewarding discoveries. Still, the possibility of unearthing the occasional gem often proves too enticing to resist; it is the same hope that motivates each visit to the archives, long days wading through homogenous archival boxes, and the unending flipping of musty, timeworn pages.

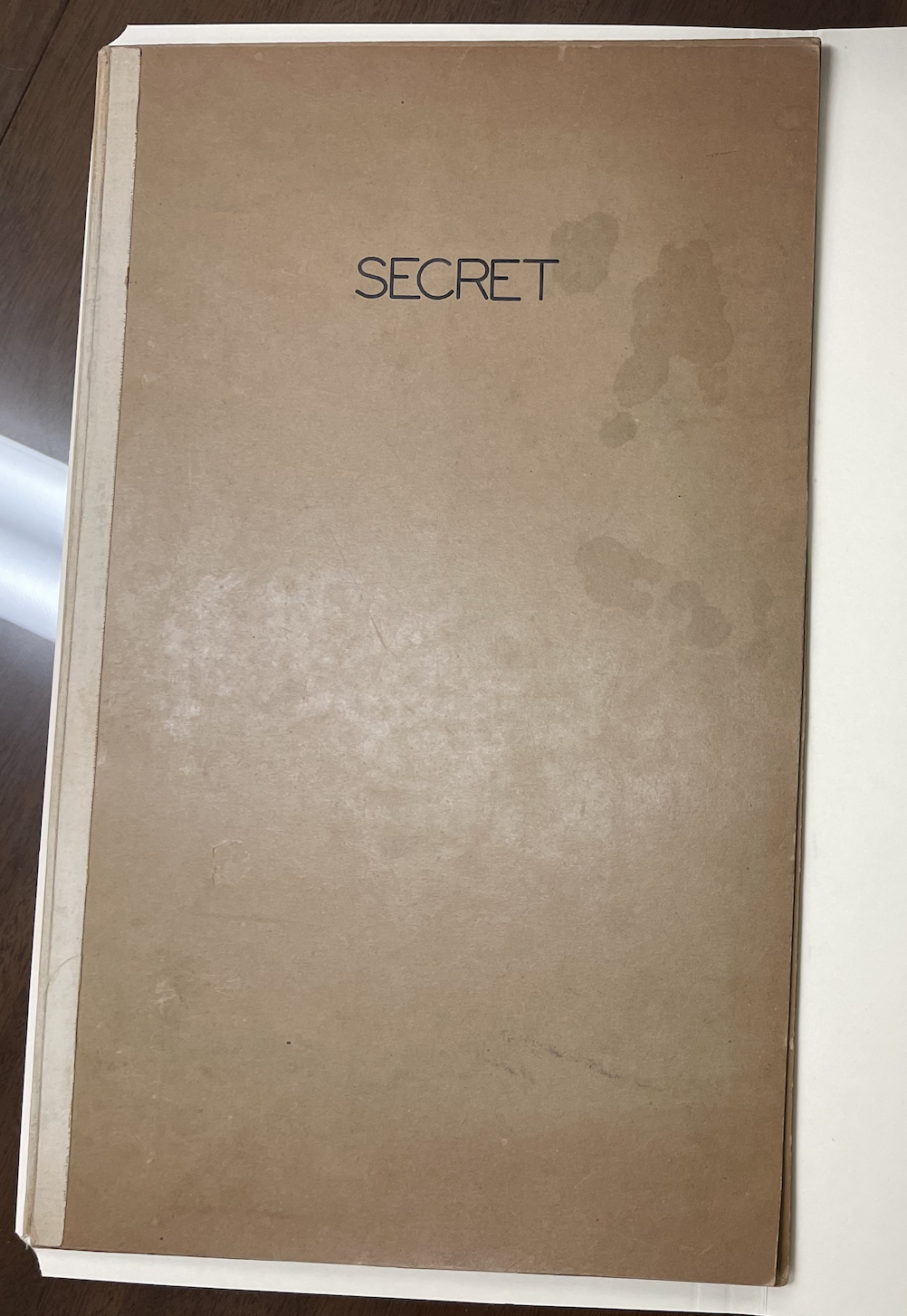

Uncovered almost anywhere else, everyday objects housed in the world’s archival repositories would likely be dismissed as antique at best—old and uninteresting at worst. And yet, an artifact’s mere presence in an archive can lend it value that otherwise might go unnoticed. Take, as one example, this innocuous cardstock folder labeled “SECRET” in bold, black letters.

Last September during our first ever visit to the George C. Marshall Research Library in Lexington, Virginia, my father and I came across this artifact in box 1, folder 23 of the Carter Burgess collection. At first glance, the folder is plain and uninteresting. Empty, lightly scuffed in places, and bearing several blemishes, on its own it offers no insight into where it came from—nor what it once carried.

Adjacent artifacts offer clues into the folder’s significance: Accompanying the secret folder are ten Italian lires inscribed with the date 9/28/43 and Mr. Burgess’ initials; there are two Maltese shillings dated 9/29/43; and there is an envelope emblazoned with a golden eagle crest of the United States. In blue cursive ink, Burgess’ own handwriting offers another glimpse into the folder’s past.

“Circa September 1943, Malta. Note: The full story of this classified folder is in an envelope on the back of this frame. Briefly: The first Italian surrender was signed in this folder aboard a British Man-of-War in Valetta Harbor, Malta. I was there! Carter L. Burgess.”

If this folder could talk, what stories would it tell?

Born on Christmas Eve, 1916, Carter Burgess graduated from the Virginia Military Institute on the eve of World War II in 1939. He married his sweetheart a month before Pearl Harbor and entered the military as a second lieutenant, rising to the rank of colonel by war’s end. His assignments took him across the Atlantic to Europe. There, he served as a staff officer and secretary to the general staff at General Eisenhower’s Allied headquarters (AFHQ)—first in the Mediterranean, then in Europe.

Burgess’ proximity to Eisenhower and his role as one of the favorite aides of Ike’s chief of staff, General Walter Bedell Smith, likely played a role in his possession of this secret folder. While its exact provenance remains unknown, the saga that preconditioned its wartime use at Malta “reads like the most improbable fiction.”1

CONTEXT

By late summer 1943, Allied forces in the Mediterranean delivered a major blow to the Axis, liberating Sicily on August 17. The campaign augured poorly for the Italian high command; aware the next invasion would likely come on the Italian mainland, many sensed the strategic initiative firmly shifting to the Allies’ favor. Prior to the campaign, popular support for Italy’s fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, reached an all-time low. Pushed to the periphery of the German agenda while Germany embarked on Hitler’s selfish crusade for lebensraum, Mussolini himself knew Italy had become little more than a junior partner in an already asymmetrical alliance. Now incapable of defending their own territory, Italian leaders recognized further collaboration with Nazi Germany portended Italy’s ruin. There was only one recourse.

While the battle for Sicily raged, a small cohort of Italian military officials laid plans to depose Il Duce. At 3:30 a.m. on Sunday, July 24, 1943, Italy’s Fascist Grand Council held its final meeting in Rome’s Palazzo Venezia. Voting 24-7 to remove their leader from his post, soldiers arrested Mussolini as he departed the palace. In his stead, Italian officials appointed Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio as head of the Italian government—a man who, having only heard about the conspiracy the day prior, nevertheless pledged to steer Italy into the Allied orbit.

It would not be easy. As the attack on Sicily intensified and mainland Italy increasingly felt the destruction of Allied bombs, vigilant Nazi officials tightened security on the peninsula, installing Gestapo agents in Rome and guards on every road of departure. It took fourteen days for Badoglio to successfully dispatch an envoy through the German security blanket; that he did manifested his willingness to negotiate Italy’s surrender and join the Allied cause.

PORTUGUESE PARLEY: SECRET ENCOUNTER IN LISBON

Traveling as part of a diplomatic delegation sent to Lisbon to welcome Italy’s ambassador to Chile on his return to Europe, two Italians bore the “difficult and dangerous mission of contacting the Allied nations and arranging to get Italy out of the war.” The first was 36-year-old Franco Montanari, the Harvard-educated son of an American mother who lived with his siblings in Vermont. Montanari spoke perfect English, previously serving as the Italian consul in Honolulu. He would act as an interpreter and political advisor to his military companion, General Giuseppe Castellano, a “short, swarthy” staff officer of Sicilian descent who rose to prominence on the staff of General Vittorio Ambrosio, a known Allied sympathizer and chief-of-staff of the Italian armed forces.

Dressed as civilians, Castellano and Montanari departed the diplomatic train in Madrid under the pretext of visiting friends. The pair immediately informed the British ambassador to Spain of Badoglio’s desire to negotiate with the Allies. The unexpected announcement prompted a barrage of Allied planning; verifying their credentials, Allied officials told both Italians to wait in Lisbon until Eisenhower could rush delegates to meet them.

Eisenhower chose his trusted lieutenant and chief of staff Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the task. A stern, square-jawed career staff officer referred to as Ike’s “hatchet man,” Smith was accompanied by Brigadier K.W.D. Strong, OBE, a bright British intelligence officer and assistant chief of staff, G-2 at AFHQ.2 Both were chosen because of their familiarity with the latest plans to invade of mainland Italy. Strong’s familiarity with the Italian language and culture also helped.

Smith and Strong departed Algiers for Gibraltar on the afternoon of Wednesday, August 18, 1943 dressed like their Italian peers in civilian clothes. Each assumed false identities and bore false passports—Smith posing as a businessman, Strong a commercial traveler. Boarding a passenger liner the next day, one-and-a-half hours later the unarmed envoys touched down in Lisbon.

To their relief, neither were recognized by Portuguese customs officers. Taking an undercover vehicle, they soon arrived at the home of one Mr. George F. Kennan, the American charge d’affaires in Lisbon—a man who within a few years would find fame as the founding father of America’s Cold War containment strategy.

Smith and Strong waited in Kennan’s home until nightfall. At 10:30 p.m., the two proceeded to the private residence of the British ambassador, Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell, to await their Italian negotiators. With Gestapo agents prowling around the city, the Italians went to meet them. They took every precaution to preserve their anonymity. After dinner in their hotel, the pair took a taxi to another restaurant for coffee before hiring a second taxi to the outskirts of the city. There, they entered a building and left out the back door—a move calculated to evade dubious company. They could not be too safe. A third taxi deposited them at the Ambassador’s residence, where they were ushered into a dim study, shutters closed, curtains drawn.

The delegations introduced themselves formally. There were no handshakes. The Americans made a point of ensuring the Italians were, in fact, Badoglio’s accredited representatives by getting in touch with a representative of the Badoglio government via a British minister at the Vatican. He confirmed their diplomatic status.

As the senior spokesman, Smith delivered the Allied terms: Italy and its armed forces would surrender unconditionally. It would recall its overseas forces immediately; it would turn over all military bases for Allied use; the Italians, thereafter, would assist the Allies as far as possible. Political and economic terms would be negotiated later. Hoping to avoid the ignominy of surrender, Castellano hoped Italy could join the Allied cause without formally admitting defeat. Smith held firm—sign the armistice, or no deal.

Following Smith’s opener, Strong took over. The conversation touched on Axis troop dispositions in Italy, the feasibility of establishing communications between Algiers and Badoglio’s government in Rome, how to secure the Italian fleet, and Mussolini’s fall. The Italians provided plenty of valuable intelligence for Allied planners. Aides in an adjacent room lent their insight and worked on the specifics of the armistice through the night.

The Italians bade farewell to their Allied counterparts as the twinkle of dawn illuminated Lisbon’s eastern horizon. Given a briefcase bearing a special disguised portable wireless capable of relaying messages between Rome and Algiers, Montanari carried the actual terms in an inside-suit pocket on his person. Reuniting with their Italian diplomatic cadre, the two traveled back to Rome through Southern France aboard a special Italian train. For their part, Smith and Strong returned to Algiers wondering whether their counterparts would make it back safely. The wait was on.

AN UNEXPECTED INTERMEDIARY

Several nervous days passed while the Allies awaited Badoglio’s response. In the interim, a “sensational new development…threw the Allied camp into a welter of doubt and suspicion.” Italian Brigadier General Giacomo Zanussi, senior officer on the staff of the Italian Army chief of staff, had surfaced in Lisbon, telling an Allied contact he was eager to discuss the terms of Italy’s surrender on Badoglio’s behalf!

Naturally, Zanussi’s sudden appearance raised eyebrows at AFHQ. Bringing with him a British general captured by the Italian armed forces in 1941 to bolster his credentials, the Allies soon discovered that Badoglio, unaware of delays imposed by the late arrival of the Chilean ambassador on Castellano and Montanari—and worried Italy itself might soon be invaded—sent Zanussi on a last-ditch mission to reach an agreement with the Allies. Little did he know, Montanari and Castellano would soon arrive in Rome bearing the Allied terms.

Forced to relinquish his British captive, Zanussi reiterated Badoglio’s concerns to Allied personnel in Lisbon. He hoped contacts at the Vatican could vouch for him. Intelligence officers in Algiers called attention to the fact Zanussi’s long-time superior, General Mario Roatta, had been military attaché in Berlin for four years and “was considered of all Italian army officers to be the closest and most sympathetic to the Germans.” He could, ostensibly, also represent a hostile faction in Italy—one opposed to the Badoglio government. It was almost impossible to know for sure.

Seeking clarity, AFHQ sequestered Zanussi to Algiers to interview him in person. After twenty-four hours of “almost insupportable tension,” on Friday, August 27, the Allies finally established contact with Badoglio in Rome. Badoglio informed Zanussi of the arrival of Castellano, Montanari, and the Allied terms. Zanussi urgently exhorted his superior to accept the armistice terms, whereafter he “faded completely out of the negotiations picture” just as rapidly as he had appeared.

ANOTHER RENDEZVOUS

Five days later, Badoglio relayed his desire to comply with the Allied terms. On August 31, Castellano arranged a meeting in Sicily to finalize the negotiations. Taking off from Rome in a plane headed toward Sardinia, the pilots diverted for Sicily, where Allied Air Forces, warned of their arrival, greeted them at the Termini airfield.

Strong greeted Castellano on the tarmac and ushered him into a khaki limousine. Driving ten minutes down the Sicilian coastline, they arrived at AFHQ’s Advanced Headquarters outside Cassibile just west of Syracuse. There, Smith, Zanussi, and several other Allied negotiators had arrived from Algiers.

Congregating in a series of tents assembled in the shade of an olive grove, armistice talks began promptly at 11 o’clock. Castellano started the discussion with a grave announcement; since the Lisbon encounter, the situation in Italy had changed. Sensing Italian treachery after the fall of Sicily, German troops were pouring into the Italian peninsula to prepare for what they viewed as an imminent Allied invasion. The Italians knew Nazi Germany could be ruthless. Badoglio’s government, Castellano explained, as well as the people it represented, naturally feared German reprisal.

Reading from a prepared statement, Castellano elaborated that Badoglio sought to delay the signing of the armistice until the Allies could guarantee protection against Germany. In the very least, a delay might allow Italy to defend itself against German forces before the occupation grew out of hand. Smith and Strong, however, knew plans for the amphibious landings at Salerno were well in the works. The invasion of Southern Italy, mere days away, would happen whether the Italians played ball or not.

Each reminded Castellano the Allies would not negotiate on a conditional basis. Their plans were firm; the Italians could join and help liberate their homeland, or wait and suffer the consequences. Aware Castellano spoke more English than he let on, Allied negotiators played up the combined Allied fighting strength—“a gigantic bluff,” noted one reporter. It did not matter. Both Smith and Strong knew knocking Italy out of the war diplomatically was far preferable to doing it by force.

That evening, the Italians returned to Rome. Irritated by Italy’s indecisiveness, they imposed a firm deadline on the Italians to provide an unambiguous answer by end of the following day. Predictably, the Italians delayed. Nineteen hours late, word arrived at AFHQ that the Italians had accepted the armistice. Castellano scheduled his return to Sicily to finalize the deal.

THIRD TIME’S THE CHARM

One final hurdle delayed the secret signing of the Italian armistice. Meeting back in the olive grove outside Cassible, Castellano vacillated once more. In a calm voice, he informed his peers that while Badoglio’s government accepted the terms, he was not authorized to sign on the Marshal’s behalf.

The announcement infuriated the Allies, who told Castellano unless he signed then and there, the negotiations would collapse. Flashing a cable beseeching the Italian government to deposit a written statement at the British Ambassador’s Vatican office authorizing Castellano to sign, strained radio operators grew incensed as atmospheric effects hampered transmission to Rome. While the negotiators anxiously waited for a response, General Eisenhower arrived and joined the party.

Finally, several hours later, a relieved wireless operator informed Eisenhower that Badoglio had indeed submitted the requisite paperwork authorizing Castellano to sign the armistice. Filing back into the dusty tent for what they hoped was the last time, sunlight poured through the trees, casting shadows on the table bearing the Allied terms of surrender.

Castellano, pulling a pen from his double-breasted suit pocket, signed with an energetic flourish, flanked by Montanari and Smith, who expressed their approval. Smith, using his own fountain pen, went next.

The momentous signing—one that likely saved tens of thousands of lives in the coming campaign through the Italian peninsula—played out to little fanfare. Sharing a cup of whiskey, the participants shuffled out of the tent. Smith and Castellano plucked branches from nearby olive trees—an appropriate symbolic gesture. Eisenhower shook Castellano’s hand and quickly departed.

THE CANCELED AIRBORNE GAMBIT

With Italy’s fate now intertwined with the Allies, leaders at AFHQ wondered how to announce the armistice terms. Within a few days, British forces would land on Italy’s toe; several days after that, the U.S. Fifth Army would slam into the Salerno coastline, south of Naples. Feeling it would be best to share news of the armistice on the eve of the Salerno landings—both to forestall German countermeasures and ensure the Italians had sufficient time to react— Eisenhower and Badoglio agreed to simultaneously broadcast the terms at 6:30 p.m. on the evening of September 8, 1943.

Now becoming a variation on a common theme, new developments threw Allied planners into a frenzy. With Allied amphibious forces in their final stages of preparation, on September 5 Castellano transmitted Badoglio’s request that American airborne units be dropped around Rome in a bid to enact the seizure of the Eternal City. They would, he promised, receive assistance from Italian troops in the vicinity. Castellano knew little of the Allied invasion, nor did he know American paratroopers were already earmarked for an operation near the Volturno River north of Naples. However, the prospect of capturing Italy’s capital was too enticing to ignore.

After a long night of deliberation, Allied leaders agreed to scrap the Volturno River drop. Left with just two days to prepare an operation that under normal conditions might require three to four weeks’ planning, the Allies needed assurances Italian soldiers would assist the paratroopers regardless of Germany’s response. For that, they needed someone to confer with Badoglio himself.

To scope out the operation’s chance of success, Brigadier General Maxwell Taylor, second-in-command of all American airborne divisions, and Colonel William Tudor Gardiner of the U.S. Army Air Forces were selected for an eleventh-hour mission to Rome. Neither Taylor nor Gardiner knew the other particularly well, but both got along well enough. Handsome, tan, slim, and perceptive, the forty-two-year-old Taylor “personified the corps d’élite that comprises the parachute divisions of the U.S. Army.” Harvard educated and ten years Taylor’s senior, Gardiner possessed equally encouraging credentials: A World War I veteran, after the conflict he had became a lawyer, later serving two terms as governor of Maine.

The heightened need for operational secrecy imposed temporal constraints on their mission. Their superior, British General Harold Alexander, informed them they could not go unless it was twenty-four hours before the paratroop operation on Rome. If captured, the Allies risked losing the element of surprise in their upcoming amphibious landings—an outcome that could result in the loss of an entire airborne division. Sobering prospects indeed.

The duo left Cassibile on the morning of September 6, 1943 with plenty of travel ahead of them. Staying overnight in Palermo, Italian agents made arrangements to receive the Americans in Rome over their suitcase-set wireless. Wearing tan military uniforms and sidearms to lend legitimacy to their mission—and render them safe from the ignominious fate befalling most captured spies—in the early morning of September 7 the Americans clambered into a British PT boat that took them to Ustica, an island forty miles off the coast of northwestern Sicily.

There, they transferred onto an Italian corvette piloted by Admiral Francesco Maugeri of the Italian Office of Naval Intelligence. He provided plenty of food and wine to maximize the American’s comfort on the pleasant, two hundred mile voyage up the Italian coast. To avoid suspicion, they planned to pose as captured aviators whose aircraft had gone down in the Mediterranean. An Italian guard privy to their plans would escort them to Badoglio himself.

Landing at the naval docks at Gaeta seventy-five miles south of Rome at 6:30 p.m., Italian soldiers stuffed the ruffled operatives into an automobile and sped away. Italian sailors in the navy yard watched with interest. They drove without stopping to the outskirts of Gaeta, where a small delivery vehicle, engine purring idly, awaited them. Merging onto the Appian Way, Taylor and Gardiner observed several roadblocks but few German soldiers on the road to Rome.

They arrived after nightfall, meandering through Rome’s streets to the Palazzo Caprara adjacent to the Italian War Office. There they waited in ornate bedrooms situated in a secure wing of the palace—an undeniable upgrade to the spartan battlefield accommodation they had grown used to. The building crawled with sentries. Greeted by the chief of staff to General Carboni, commander of Italian troops in the Rome area, the Americans were soon feted at a luxurious feast by Italian officers oblivious to the imminent Salerno landings.

Wiling away the precious hours with toasts and invitations to converse deep into the night, the frustrated Americans grew worried they might overstay their welcome. In less than twenty-four hours, the world would know of the armistice; shortly thereafter, Allied troops would disembark at Salerno. Their airborne operation, scheduled six hours ahead of the amphibious landings, were now just over a day away. They needed to speak to Carboni and Badoglio!

After conveying their apprehension, Carboni arrived to greet the Americans. The two asked for his impression of the prospective operation. He expressed serious reservations. More German troops arrived by the day. News of the armistice would undoubtedly result in Rome’s immediate and urgent occupation. The Germans would, in turn, seize and reinforce its neighboring airfields. They controlled all fuel, supplies, and ammunition in the region. Consequently, Carboni noted, his forces could only fight for a few hours—at most. An airborne landing made in such conditions would be nothing less than a suicide mission. Worse still, Carboni begged the Americans to delay the armistice announcement, if only to forestall the establishment of another Fascist government in Rome.

Discouraged by Carboni’s appraisal, the Americans convinced their hosts to grant them an audience with Marshal Badoglio. Winding down Rome’s dark streets to Carboni’s limousine, jumpy sentries stopped the group eight times during the subsequent twenty minute drive to Badoglio’s villa. Air-raid sirens wailed in the distance, and angst permeated the vehicle as it pulled up just after midnight. The fate of an entire airborne division—and perhaps the armistice itself—hinged on Badoglio’s word.

The Americans found the Marshal awake, in his pajamas, surrounded by aides scurrying about the villa’s well-lit foyer. Ushered through ornamented marble halls to an upper-level study, Taylor, unable to speak Italian, addressed the Marshal in French—a language Badoglio partially understood. Gardiner took notes on “what turned out to be a very tense, short interview.” Summarizing Carboni’s dour impressions, Taylor found the Marshall in agreement. “If I announce [the armistice] tomorrow night,” he worried, “the Germans will cut my throat the following morning.”

Aware he was now acting in a diplomatic role far beyond his military rank, Taylor reminded the Marshal of his obligations to uphold his end of the armistice. An emotional Badoglio shot back. He did not believe the Allies would punish the Italians for wanting to wait for the right moment to cast their lot against the Axis. They only wanted to keep their people safe, after all.

Taylor countered. Italy was already under dual occupation, he argued—the Germans in the north, and now, the British advancing up the toe in the south. Allied bombings would intensify the longer Italy remained an active belligerent. Soon the Americans would arrive in force. There was no time for delay; the Marshal had the power to save thousands of lives. This armistice would almost certainly pave the way for Italy’s liberation. Badoglio held firm.

Taylor encouraged Badoglio to draft a message to Eisenhower outlining his position. Taylor, meanwhile, composed a message of his own, urging Allied officials to postpone the Rome airborne operation. At the close of their meeting, Badoglio clasped Taylor’s hand in his own and, looking him in the eyes, pledged “by my honor of fifty-five years as a soldier my loyalty to the Allied cause.”

Atmospheric interference once again delayed the delivery of Taylor’s critical message. Dispatched at 1:21 a.m., it arrived more than four hours later on the morning of September 8. Allied leaders at AFHQ received it on their desks several hours after that. Having already foreseen the possibility of a botched airborne operation, AFHQ forwarded a codeword indicating its immediate cancellation: “Innocuous.” Taylor waited for this response for hours. None came. Sleeping fitfully and waiting through the night as the sound of American bombers roared overhead, General Carboni finally informed the two Americans their messages had been received at 11:35 a.m., much to their relief.

By 3:30 p.m., plans had been arranged to smuggle the Americans out of Rome aboard an outgoing transport plane. With the armistice declaration just three hours away, on his way out Taylor reminded Badoglio of the consequences if he failed to live up to his word as a soldier. Taking an undercover vehicle out along the same route they had taken into Rome, the group boarded an Italian bomber parked on the runway and took off.

The mission was an unequivocal success, but only just. By the time Taylor’s message had filtered down the Allied chains of command, “the paratroops were already on the field, set for take-off.” That evening, Badoglio delivered on his word—albeit, predictably, an hour-and-a-half late. Announcing the armistice on Radio Rome at 8:00 p.m., he fled the city early on September 9 alongside Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III, finding refuge among the British forces at the port of Taranto.

FINALIZING THE ARMISTICE: THE ITALIAN FLEET AND THE SECRET FOLDER

These unbelievable scenes preceded the armistice’s final act: The surrender of Italy’s powerful navy in the aftermath of the September 8 radio announcement. With more than two hundred vessels in its fleet, Allied leaders worried that in the chaos to follow, Italian naval officers might be encouraged to resist the Allied landings, scuttle its ships, or turn them over to the Germans. To avoid this outcome, they worked a clause into the truce calling for all Italian naval personnel to sail for Allied ports after the announcement—those on Italy’s west coast were directed to North Africa, and those at Taranto, to Malta.

Most Italian admirals knew nothing of Badoglio’s armistice until his broadcast on September 8, 1943. Luckily, the Italian admiralty complied with the terms, setting sail “after a near mutiny” on September 9. The next day, the first Italian vessels laid anchor off the Maltese coast under British escort.3 More warships and submarines arrived over the ensuing month, each pledging to collaborate with the Royal Navy to bolster Allied naval power in the Mediterranean.

On September 29, 1943, the Allies held a formal ceremony on the deck of the British battleship HMS Nelson, anchored in Malta’s Valetta Harbor. The meeting would publicly ratify the complete terms of the Italian armistice, negotiated and signed in secret several weeks earlier. On the deck, Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio, dressed in his Italian uniform and cap, conferred with General Eisenhower and other Allied leaders.

Among them, porting the detailed armistice terms they would sign in an innocuous cardstock folder labeled “SECRET” in bold, black letters, was Carter L. Burgess.4

Oh, if that folder could talk, what stories would it tell?

Clark Lee, “The Story Behind Italy’s Surrender,” n.d. and David Brown, “The Inside Story of Italy’s Surrender,” Parts I and II, Saturday Evening Post, n.d., Box 1, Folder 9, Carter Burgess Collection, George C. Marshall Research Library [Hereafter GCM], Lexington, Virginia. All citations hereafter from these sources unless otherwise noted. ↩︎

Robert D. Murphy, oral interview by Jean Smith, February 23, 1971, transcript, 1973, Eisenhower Administration Project, Columbia Center for Oral History, 6–7. ↩︎

Joseph Caruana, “Malta’s Role in the surrender of the Italian battle fleet to the Allies in September 1943,” Times of Malta, January 18, 2014. ↩︎

For the terms themselves, see “Armistice with Italy: Instrument of Surrender; September 29, 1943,” The Avalon Project, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. Accessed on November 18, 2021. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/italy03.asp ↩︎